The initial, biologically baffling findings were published last year in the journal Nature Geoscience. They came from several expeditions to an area of the deep sea between Hawaii and Mexico, where Prof Sweetman and his colleagues sent sensors to the seabed – at about 5km (3.1 miles) depth.

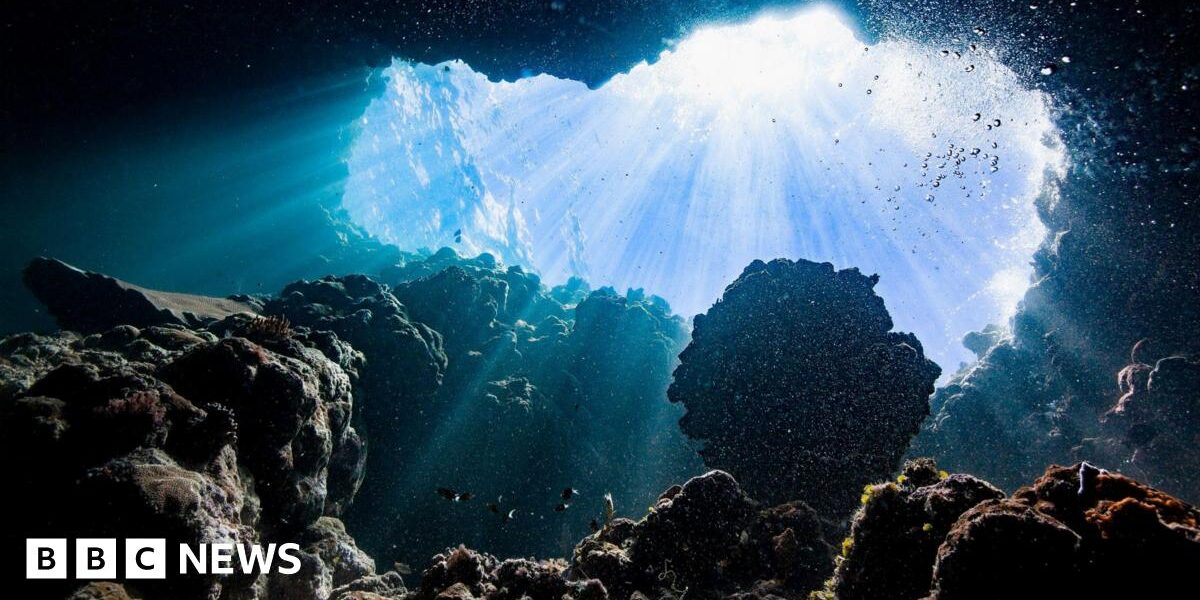

That area is part of a vast swathe of seafloor that is covered with the naturally occurring metal nodules, which form when dissolved metals in seawater collect on fragments of shell – or other debris. It’s a process that takes millions of years.

Sensors that the team deployed repeatedly showed oxygen levels going up.

“I just ignored it, Prof Sweetman told BBC News at the time, “because I’d been taught that you only get oxygen through photosynthesis”.

Eventually, he and his colleagues stopped ignoring their readings and set out instead to understand what was going on. Experiments in their lab – with nodules that the team collected submerged in beakers of seawater – led the scientists to conclude that the metallic lumps were making oxygen out of seawater. The nodules, they found, generated electric currents that could split (or electrolyse) molecules of seawater into hydrogen and oxygen.

Then came the backlash, in the form of rebuttals – posted online – from scientists and from seabed mining companies.

One of the critics, Michael Clarke from the Metals Company, a Canadian deep sea mining company, told BBC News that the criticism was focused on a “lack of scientific rigour in the experimental design and data collection”. Basically, he and other critics claimed there was no oxygen production – just bubbles that the equipment produced during sample collection.

“We’ve ruled out that possibility,” Prof Sweetman responded. “But these [new] experiments will provide the proof.”

This might seem a niche, technical argument, but several multi-billion pound mining companies are already exploring the possibility of harvesting tonnes of these metals from the seafloor.

The natural deposits they are targeting contain metals vital for making batteries, and demand for those metals is increasing rapidly as many economies move from fossil fuels to, for example, electric vehicles.

The race to extract those resources has caused concern among environmental groups and researchers. More than 900 marine scientists from 44 countries have signed a petition, external highlighting the environmental risks and calling for a pause on mining activity.

Talking about his team’s latest research mission at a press conference on Friday, Prof Sweetman said: “Before we do anything, we need to – as best as possible – understand the [deep sea] ecosystem.

“I think the right decision is to hold off before we decide if this is the right thing to do as a a global society.”